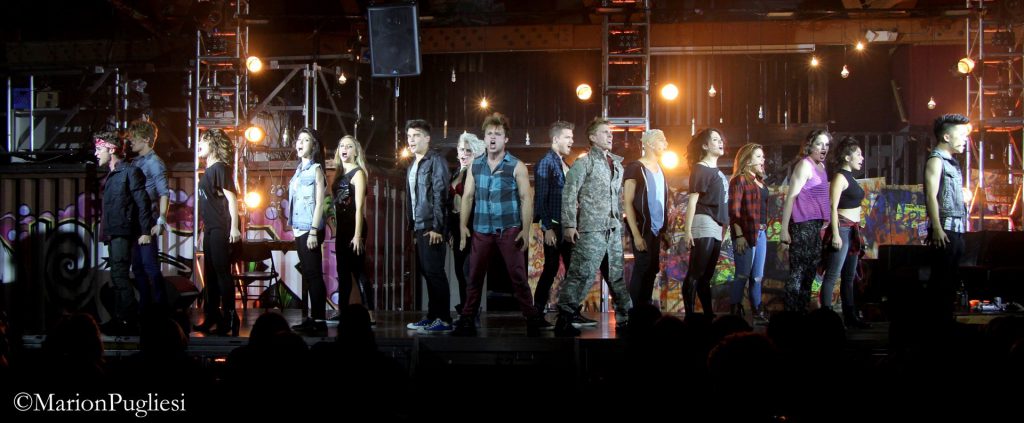

Brandon Baruch’s Scenic Storytelling

Posted on September 28, 2017

Photo: Michael Amico

Before Brandon Baruch makes his final decision about how to light a set piece on stage, he likes to spend time alone with it, “listening” to what it has to say about itself. In his view, every scenic element has a distinct personality, interacting with its surroundings in its own unique way. Understanding and appreciating this interaction is the first step toward lighting an object in a way that harmonizes it with a production’s overall design.

Baruch has used this interactive approach to create stunning panoramas, turning scenic elements from mere props to full partners with lighting on stage. Impressed with his work on projects like the Bataré tour and Hollywood Fringe Festival, we sat down with him to talk about scenic storytelling.

It seems that even in non-theatrical productions like concerts and recitals, we are seeing more artistic scenic elements – i.e. pieces that go beyond standard screens, curtains and risers to include more dramatic visuals. How does this change your approach to lighting that kind of production?

“I use the same design approach for most types of live performances regarding lights and scenic elements. I start by asking: what is the story we’re trying to tell? A concert or dance show might not have a narrative, but I can still usually hone in on its emotional arc. I get excited by scenic objects with unique textures and shapes that can receive light in multiple ways. The storytelling comes from letting the audience think they understand what they’re seeing, then allowing new and unexpected visuals to emerge before their eyes.

“It’s kind of like a really good magic trick. It’s exciting when a tiger appears in an explosion of sparks and smoke on stage, but it’s so much cooler when you think you’re going to see a card trick. You think you know everything that’s going on, and them BAM a tiger! I always start my concert designs with a simple lighting schema. I let the audience study it, understand it, and ultimately ignore it. Then it’s that much more impactful when the scenery and lighting combine to create unexpected visuals.”

From the lighting perspective, what’s the key to accenting the artistic side of a scenic element so you create this sense of surprise?

From the lighting perspective, what’s the key to accenting the artistic side of a scenic element so you create this sense of surprise?

“You have to reveal the object for what it is rather than try to force light on top of it.”

Do you try to include artistic scenic elements in your designs, even if they are not already included in the original concept?

“I like to work closely with scenic designers from the ground up whenever possible. I think that the best collaborations are the ones where you can’t tell where one designer’s work begins and the other designer’s work ends. I’m also unabashedly obsessed with the architecture and personality of household and industrial lighting fixtures, so if it fits the story or aesthetic, I often look for opportunities to integrate them into the scenic design.”

How do you balance the idea of creating artistic visuals on stage without detracting from the performance itself?

“It’s usually not an issue for me, since I always concentrate on telling the story of the piece above everything else. I’m in a really lucky spot with my career where I get hired to design a diverse assortment of projects, so I rarely feel the need to do showcase work. My favorite designs are those where I’m just one more cog in an incredible machine. If my work is the most noticeable element of a production, I’ve done something very wrong.”

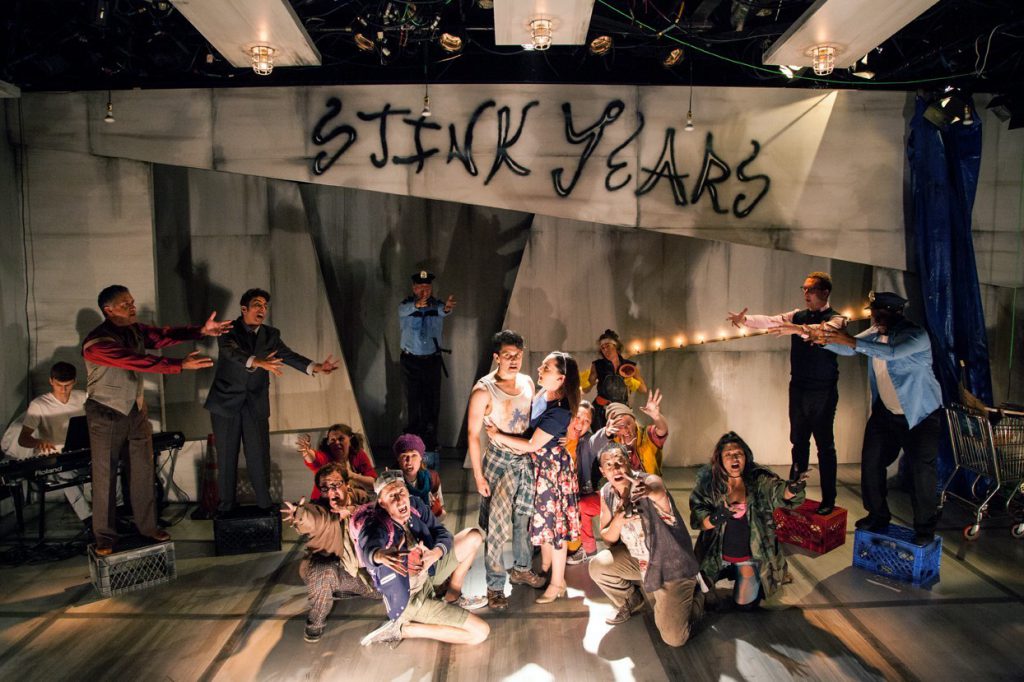

Photo: Nardeep Khurmi

We’ve seen you light scenic elements from every direction: uplight, downlight as well as from the inside. Are there general rules that you would follow concerning when you uplight or downlight a scenic element? How do you determine when to do one or the other?

“It definitely varies from piece to piece. Different lighting angles have distinctly different advantages. Do you want to expose the fixture? Where is the light spill ultimately going to land? As far as inside/outside goes, that’s mostly about whether or not you want the object to be in the same universe as the performers. Because if you light an object from the outside, the performers can interact with it by walking between the source of light and the scenic object and creating shadows, whereas if it’s lit from the inside, it has a more magical, otherworldly quality.

“Also, it depends on the texture of the piece. If it’s a flat object, I might try to front or backlight it. But if it has a stipple or brick texture (for example) I will come at it from an extreme angle in order to emphasize the shadows its texture creates. Another thing that’s important to consider is how you want to reveal dimension. Side light creates drastically more dimension than front or backlight. By controlling the amount of dimension you reveal, you can also control the way the audience perceives the depth of the performance space.”

Any other comments about lighting from the inside? Any thoughts on when and why a designer should do that?

“The main advantage to lighting from the inside is that you have the cleanest control over light spill.”

In your work for the Bataré tour, you turned instruments (Taiko drums) into artistic elements with your lighting. Is this something you try to do- take an instrument or other object that’s on the stage and use lighting to bring out its ‘artistic’ side?

In your work for the Bataré tour, you turned instruments (Taiko drums) into artistic elements with your lighting. Is this something you try to do- take an instrument or other object that’s on the stage and use lighting to bring out its ‘artistic’ side?

“In that show, the Taiko drums felt like cast members more than scenic objects. The connection between drum and drummer was organic and reciprocal – neither could exist without the other – so when I lit the drums, it was imperative they existed in the same world as the performers. In general, I like to design for the back row of the theater, and the full composition of the stage is an important consideration. For this production, I wanted the cast and drums to all blend together into a singular drumbeast that felt larger than the stage it was on — And to be honest, those drums were so beautiful and intricate, it would have been a crime not to give them a little extra loving.

Also on the Bataré tour, you lit your risers to create abstract patterns on them, giving them a more artsy appearance. Can you describe what you did there?

“For that tour, we have a milk plexi fronting on all of the risers and platforms. I backlit each square with a COLORado Quad-Tour, then programmed various color chases, strobes, and effects across them. I also placed clear plexi squares on the top corners of each platform with SlimPARs underneath to create columns of colored light. The lighting on the risers dances with the performers, which again helps in creating a single cohesive performance creature on the stage.”

Photo: Stephanie Fishbein

Looking at another one of your projects, Hollywood Fringe Festival, where you lit balloon art. Can you tell us how you approached that project?

“The Hollywood Fringe Festival Closing Awards are always a crazy challenge – we get about five hours in the space to build and tech the show on a shoestring budget. The balloon art was a happy accident. I was basically just programming an assortment of palettes and presets for the moving lights in the house rep plot when I realized how amazing the texture looked on the balloons. I locked in on that and went with my gut.

“There will always be projects that require intense preplanning, paper techs, Q sheets, even visualizes and WYSIWYGs, but my favorites are the ones where I get to experiment and play. The Fringe Festival very generously lets me run wild with my design, so every year I try to do something new, unexpected, and a little goofy.”

When you start a project and there is an artistic scenic element on the set like the balloons at Hollywood Fringe, are there any particular features about that object that you consider first when deciding how to light it?

“It sounds so corny, but I have to listen to the set piece and let it tell me how to light it. It’s always good to have a plan, but until you’re in the room, there’s no way to really know. When I start interacting with a scenic element, I try to turn my brain off and just go by instinct. Once I’ve discovered how to best play with the scenery, I turn my brain on again and go back into storyteller mode.”

Any thoughts on blending video walls with scenic elements?

“I have to tread delicately here, because I have some close friends who are very, very, very talented video and projection designers. I think that when properly realized, video design can be a dynamic and important part of a production. But when it’s thrown on top of a show instead of integrated with the other design elements from the start of production, it has the potential to obfuscate the other design work happening on stage.

“I will say that a personal pet peeve of mine is when you have a beautiful, detailed scenic design with a big flat screen in the middle for video. Because either you always have to have the video on, or else when it’s not running, you have a fat bald spot on the stage. Again, though, I’m coming from a theater background. In music concerts I guess it’s fine. Although it still doesn’t feel as exciting as actual scenic elements.”

Any other thoughts or advice you want to give on creating more artistic set designs?

“I guess I would mention that bigger is not always better. A simple yet striking gesture might do the job better than an expensive and over-complicated design. Let the piece tell you what it needs, then honor those needs. The rest will take care of itself.”

Photo: Kyle Breen