Martin Thomas – Living Light

Posted on December 3, 2019

Photo: Todd Kaplan Photography

Emotions are magnified in the darkness. Perhaps this is why negative space has always played such a significant role in this native New Yorker’s designs for Grammy Award winners like The Alan Parsons Project, D’Angelo, Erykah Badu and Jill Scott. Among the things he likes most about working a live performance is “calling the house to black” as a show is about to begin. There in the dark space, he can feel the waves of energy ripple through the crowd and is reminded once again why, even now after so many tours, he still prefers to run his own board.

Lighting is a living, breathing thing for Martin Thomas with power to transform space and convey deep emotions that cannot always be translated into words, or music. This is why he will often make modifications to a design during a tour, adding new cues here, removing a fixture there, all in the pursuit of better reflecting the essence of his clients’ experience — and not merely their sound.

Experience must inform the creative process, believes Thomas. In his own case, recent events have added a more reflective dimension to his design philosophy. In 2017, in the middle of a Todd Rundgren tour, he suffered a detached retina with a macular hole and went completely blind in one eye. Surgery and extensive rehabilitation followed. Doctors didn’t know if he would ever regain his vision in the affected eye.

Eventually his vision was restored, and he went back on tour, pursuing a quest that had long since become “more than a just a job.” Speaking to us from the Tucson, AZ office of his company Relentless Entertainment Design, Thomas shared his insights into the life force of light and lighting design.

Photo: Tabitha Parsons

When discussing your design for The Alan Parsons Project’s recent European tour, you used the term “atmospheric architecture.” How would you define that and why is it important?

“From a non-scientific standpoint, I’ve always seen lighting as a structure – something with an architectural quality. This may be the beam of sunlight through a window of a dusty church, the glow of a horizon line with a mountain range in the foreground, the cut of a well-focused ellipsoidal falling from the heavens of the second cove. Whatever form it takes, lighting has always possessed physical properties for me.

“Controlling the application of lighting through good design, allows you to structure a three dimensional image for the audience, and in some cases the artist too, that resembles architecture. This idea has been an important part of my design concept since I started doing this in school. Making light become a tool to create a pillar, an environment, a frame, through the use of intensity, focus, color and negative space, is what I see as the foundation of all of my productions.”

Can you elaborate on how you go about creating this architecture?

“It all starts in the initial design process. Once a concept is solidified with the client, the engineering design process begins. That’s when you focus on things like where fixtures need to be, what type of equipment will accomplish the desired outcome, how does that equipment hang, and what will it ultimately do when used alone or within a group? Just as the architecture of a home or building should reflect the personality of the person or company that resides within, the proper lighting design should be a representation of the musical artist, or a theatrical presentation as envisioned by the writer or director.”

Photo: Todd Kaplan Photography

Can you share an example of how this process works for you?

“My work with Erykah Badu drew from her background in dance and theatre. My work with Alan Parsons has reflected the era of his musical catalog, concentrating on the technologies that were an important part of the prog-rock genre, a kind of a tech-based, art-meets-science. As is the case with all of my clients, both of these artists give me so much to draw from when creating designs. Drawing on their inspiration, I create the structure, or ‘the architecture,’ for the production, not only in terms of the physical set pieces and line sets, but also in terms of how the structure of the light plays with the elements of the stage and venue.”

Color has always played an important role in your designs, particularly as it conveys moods. Have you changed the way you use color over the years?

“Color, particularly saturates, have been a big portion of my approach to design as a touring LD. Music is emotional; the ability to understand, translate and transmit that emotion visually through light has been one of the most enjoyable parts of my time as a designer. I get so much satisfaction out of an asymmetrical color visual, especially on colors that don’t see much use in many shows.

“I love getting a new swatch book of gel or Pantone and look at combinations that dial right into what I have envisioned for a particular song and having that read properly on stage with the right fixture. Something as simple as a side wash in R59 on one side and a L156 in a 6×16 on the other, like I did with D’Angelo in 2000 to bring out the structure of his physique and skin tone, while keeping it subtle enough to lend some mystery to the overall look. This is where color is a driving force in the design of particular moments. Color touches emotions, and is critical to the subliminal effect of speaking to the audience.”

Photo: Todd Kaplan Photography

Earlier in your career you worked with some of the leading designers like Roy Bennet, Peter Morse, Jim Chapman and Howard Ungerleider. What was the most valuable bit of advice you ever got from another designer?

“Every one of the designers I have had the pleasure to work with has imparted a bit of their wisdom to me whether they knew they were doing it, or not. I found early on that to be aware is to be the recipient of an education. By listening, I learned things as subtle as Roy Bennett’s personal style, and Peter Morse’s rapport with the artist and management. Jim Chapman and Robert Roth impressed upon me that this is a business — this at a time when the industry was in its adolescence. Personal relationships with designers like Cosmo Wilson and Bryan Hartley showed me that life is made up of many elements, and you should stop and appreciate all you can. Howard Ungerleider probably has had the most influence on me, as he was indirectly responsible for me taking the leap into making this a career and I am proud to now call him a friend as well as a mentor.”

Even earlier, your first real gig came touring with a Doors tribute band. We understand you even got a compliment from the original Doors keyboard player Ray Manzarek. From a lighting standpoint, is it different lighting a touring band that an original act?

“That particular tribute act was my first attempt at design; although I worked from existing equipment already in possession by the act. Back in the early 80s, it was quite a bit more difficult to do video research on musical acts. Digging up VHS footage of The Doors, beyond the often seen videos from the Hollywood Bowl and New Haven, CT show, took quite a bit of research. Luckily, my younger brother Christopher was a huge fan and had amassed a pretty good collection of items I could use for reference.

“I repurposed the equipment we had to resemble more of the original act’s stark lighting looks and 60s era feel. Combined with some absolutely archaic overhead, 8 mm and slide projectors, this lighting allowed me to immerse the act in the Joshua Light Show style. I was attempting to recreate an era based on historical research. I felt that was important to the presentation of the act to represent the moment and the vibe.”

Photo: Designer

Speaking of your creative design process, you came up with some very impressive looks for Todd Rundgren when you endowed the stage with a captivating depth by alternating different patterns of light and dark space. Can you describe what your thinking was with that design?

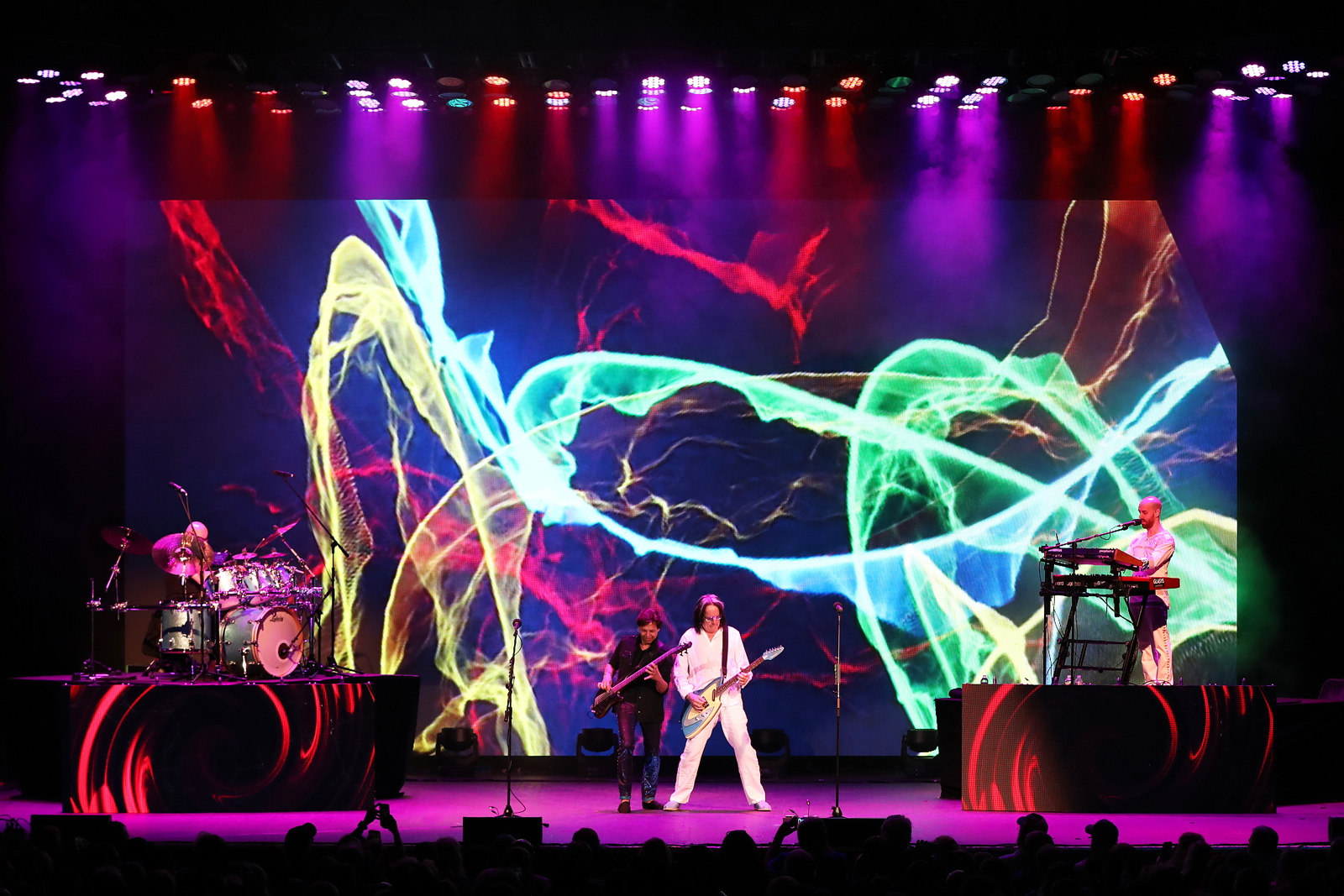

“In 2015, it was the GLOBAL Tour, with a modular stage presentation that featured Todd, two dancing backing vocalists and a DJ on a center-stage riser. Video was used to fill up the environment with anywhere from four to six towers and the graphics and lighting were designed around Todd’s theme of global consciousness and social awareness.

“In 2017, we expanded upon the video-driven production concept for the WHITE KNIGHT Tour, which featured a 32’x16’ high resolution wall upstage of the band risers and another 32’x16’ 10 mm blow-thru wall downstage of the band risers that effectively acting as a scrim, but behind Todd and the backing vocalists. Video was synced to create an immersive 3D effect for most of the graphics while silhouetting the band. Alternately, during some moments, the high res was blacked out and the 10 mm ran imagery and the band was lit from the top, side or ground to allow them to interact with the graphics from behind the semi-transparent surface.

That tour was one of my most enjoyable runs, as many of the graphics were designed by my son, Avery, who assisted me on the final days of the run. The art ranged widely from bold, dark elements, assisting in the continuation of the negative space theme, to bright and whimsical for the more upbeat numbers. It has always been a pleasure to work with Todd on his productions. He has always been a huge innovator in the visual music world, and is extremely intelligent in regards to the technology that is available to not only create content, but to drive the imagery in different ways than are commonly used in our industry.”

Photo: Tabitha Parsons

On the subject of darkness, or negative space, what role do you see it playing in your designs?

“Negative space is critical. It allows light to have a contrasting surface or environment that creates dimension. Darkness allows you to reveal a moment, or to create mystery and invisibility. My favorite part of a live performance is calling House To Black, and getting that rush when the audience has their first exciting thrill of what is coming. There’s that big cheer and then you bring out the first look to start the show out of the darkness.

“Darkness is part of my active palette. It allows me to accentuate the subjects and areas necessary to complete the big picture. Silhouette and shadow can only occur with darkness, and when used properly, they allow the light to become an effective, structural tool.”

Photo: Todd Kaplan Photography

Turning back to the Alan Parsons Project for a moment, we’ve been impressed with is how you manage to key light all the members of band without losing the sense of cohesiveness on stage. How do you do that?

“I present Alan with the proposed vision for the tour and always consult with the Production Manager for logistics of backline and staging, as well as the requirements of the musicians in regards to sight lines and elbow room. This allows me to design a space they can all work within. It’s a bit of choreography for an act that shies away from the traditional idea of being choreographed.

“Once that has been set, I do key and back lighting for an act with eight singing members, five of whom sing lead on various songs. My intention here it to ‘cut the band members out’ on stage so they pop. Over the years, this has been accomplished with the standard lighting discipline and fixtures, mostly ellipsoidal units.

“More recently I have relied on intelligent fixtures to cut down on any in-the-rig time by technicians and focus crews, although in many of our one-off performances that we are reliant on conventional house rigs. Once I have that element designed into the system, the remainder of the design is created to provide effects and moments. This embodies all of the aspects of the aforementioned architecture as well as general illumination that is pleasing to the eye and is appropriate for the production.”

You’ve been on tours in various capacities with a wide range of artists. How much does the vibe back stage vary depending on the artist who’s touring?

You’ve been on tours in various capacities with a wide range of artists. How much does the vibe back stage vary depending on the artist who’s touring?

“We, as the crew, become family. It is necessary to have that bond, as so many moving parts rely on one another for a successful production. And with the advent of social media sites like Facebook and LinkedIn, it has been substantially easier to keep track of those that you work closely with over the years.

Lately, it has also been difficult for some of the long-term career guys like myself to see those that we have lost; it is like losing a family member in many cases. We can easily feel sorrow for their immediate family and friends, and we have more than likely been in their shoes, for the most part- good and bad.

“Hard living, harder working, over-the-top plus-sized experiences that would take down the average person make up gigantic chunks of our lives in this industry; it bonds us together. Backstage life for crew is built upon the intent to hold things together, for at least the 12 to 18 hours of the day that the show occurs, for weeks, or even months, at a time. It makes it that much harder to relate it to the erroneous vision that many outsiders have of the backstage vibe, with debauchery and excess being the expected norm.

Given what you just said, why do you continue to tour a lot and run your own boards, rather than designing a show and having someone else run it?

“It becomes very personal with me, putting together a production. I am not looking at this as a job at this point in my career. It absolutely has to mean something for me to give my art to an artist for their music. It has taken a serious medical situation to get me just to stop being part of the assembly of the actual system- I really enjoy being hands-on in the construction of the rig every day, but that comes from my love of working on dragsters most of my life. I am a nuts-and-bolts person, and I find it therapeutic to be part of the build.

“However, I have, many times for a variety of clients, handed off a tour to a board operator, but it has to come at the right time. It can’t just happen once the design and programming are finished. The physical rig shows you so much more than things in pre-vis can — and I want to know that my creation is giving all that I can pull out of it before giving it over to someone else to drive. That way, when the operator comes with something they want to try, I can either investigate the new possibilities, or let them know that I have tried it already and it didn’t quite fit for our particular application. I have some very capable operator/programmers on my team, but there have been a few times where I have been burned by something as unpredictable as not having the right personality in place for the production, and the show has lacked because of that.”

Photo: DJ A1

Do you punt a lot of tour?

“Depends on the tour. I find that punting, particularly on house rigs that I don’t have a lot of time to entirely dial in for our needs, makes quite a bit of sense. I can always get the basics in, plus it’s sometimes fun to experiment and come up with new things that can be applied into the regular rig. There is always a bit of punting going on in all of my shows. Todd Rundgren is always pretty well structured in a cue-to-cue fashion, particularly in the past few solo tours and the Utopia Reunion run, but almost all the accenting is done live at the moment.

“Alan Parsons touring design is programmed for all the songs in the active catalog, and is run similar to Todd’s show in regards to the accenting. But so many of Alan’s shows are on one-off or house rep rigs that punting turns out to be more efficient than trying to replicate the tour cueing every day. I’ve been with him 15 years now, and really have a feel for the timing of the music, thanks to his superior band of musicians. Erykah Badu was almost entirely structured punting, as the show was driven by the whims of the artist. Jill Scott was a series of constructed looks built to run live.

“I have been the operator/programmer of straight cue-to-cue productions, and although they have been beautifully cued and impeccably timed, they come across as sterile, almost like how a fashion model parades a dress on the runway — and they fit the show appropriately. My personal belief is that some shows still deserve the actions of a live drive.”

Photo: Todd Kaplan Photography

You’re a native New York and a graduate of The High School of Art and Design. How did growing up in the city influence your approach to lighting design?

“I studied Architecture at Art & Design, primarily for the drafting discipline. My desire was to become an automotive design engineer, and go to work for General Motors or Chrysler. The course allowed me to study in one of the world’s most beautiful and diverse cities, from an architectural standpoint, and understand what makes up timeless and ever-changing design theories.”

You lost your sight in one eye, had serious eye surgery and didn’t know if you’d ever regain your sight fully. How did that influence your outlook on life and design?

There was quite a bit of introspective meditation that was necessary to calm myself back to where I could make logical decisions. Initially, none of the decisions I was making were in my best interest. I have to wholeheartedly thank my partner, Missy, for really grabbing the reigns of a wagon that was heading off the proverbial cliff. She really gave me the strength to continue with all the prescribed recovery and procedures that the surgeons said were necessary, if I was going have any chance of regaining any sight in the affected eye.

“Although I was unable to travel at all during my convalescence for six months, I did continue to design in my studio, working with Michael Gionfriddo, who had taken over the remainder of the tour as operator on the Todd WHITE KNIGHT run when I went into the Parsons I ROBOT 40 European tour. Michael and I worked on the summer Todd run design with YES.

“As the recovery period seemed to drag on, the people closest to me kept me focused and on-track. I do realize now that there are several concepts in my head that I’d like to come to fruition on the stage before I actually step away from touring work. There are artists I’d like to work with and visions I’d like to see become reality from FOH, as opposed to sitting in my design studio exclusively. I have also put a lot more focus on my true post-industry life, my ‘retirement,’ wherever that leads Missy and me.”

Is there a Martin Thomas design look?

“Many of my associates like to joke that when I create a design that lends itself to symmetricity, they’ll ask if I’m feeling okay. If there was a Martin Thomas design look, it would be to have the entire structure, from truss and fixtures, to beam patterns and negative space, all sync together to create a cohesive visual that transmits the energy of the event throughout the entire space. I want that energy to be apparent from the moment the audience enters the room; I think a successful design for me is when the client walks in the venue for the first time and, before the system is turned on, feels that the visual is absolutely on-target just by the way the it hangs.

How would you like to be remembered as a lighting designer?

“As someone who brought the event as envisioned to life, for both the artist and the audience, and accurately portrayed the environment in a visual manner that was both appealing and emotionally appropriate. I would hope that any wisdom I may have imparted to someone over the years has given them the ability to take the next step in their own career.”